|

|

|

|

Vegetable crop rotation is necessary for long term success in commercial vegetable production and home gardening. Knowledgeable vegetable growers who use correct crop rotation actually increase the productivity of their farms over many years of intensive cultivation. New gardeners soon learn that certain vegetables, planted year after year in the same plot, become diseased and decline in productivity.

The word "rotation" describes

the circular motion of a wheel or shaft. Rotation also describes

a planting system in which the vegetable plantings are arranged

in a sequence to improve soil health and produce high quality

and yield from year to year. Factors which interact to reduce

garden potential when rotation is not employed are: increased

soilborn diseases, nematodes, and soil insects; lower organic

matter, more chance

of toxic chemical residues, and imbalance of essential mineral

elements.

In a rotation, vegetables are often arranged

according to families so that individual vegetables from the same

family do not follow each other in the rotation. The reason

for this is that each family of vegetables has unique effects

on conditions which reduce garden potential. For instance,

most vegetables within a given family usually fall prey to the

same diseases and insects. Most of the vegetables planted

in this region belong to ten distinct families. It is important

to know that the pea or legume family includes peas and beans

of all kinds.

Beets, chard and spinach belong to the goosefoot family.

The mustard family has many members: cabbage, collards, brussels

sprouts, kale, cauliflower, broccol, kohlrabi, rutabaga, turnip,

cress, horse-radish, and radish. Carrot, parsley, celery,

and parsnip all belong to the parsley family. The nightshade

family encompasses potato, tomato, eggplant, and pepper.

The gourd family claims the vine crops: summer squash, winter

squash, pumpkin, watermelon, cantaloupe, and cucumber. Chicory,

endive, saisify, dandelion, lettuce, Jerusalem artichoke, and

globe artichoke are all included in the composite family.

The Lily family includes onion, garlic, leek, and chives.

Sweet corn is a member of the grass family, and last, but not

least, is okra which is claimed by the mallow family.

In a small acreage, or home garden it is often possible to rotate families of vegetables where only a few plants of each kind are planted. For example: tomato, pepper, eggplant, and potato can be treated as a single group in a rotation.

Common vegetable diseases that survive in soil and attack vegetables can be prevented by timely rotation. Fusarium root rot fungus infection will increase in beans and peas unless there is a span of two to three years between plantings on the same plot of land. Cabbage disease club root, caused by a fungus, will infect subsequent crops in the mustard family for a period of four to five years. A planting of broccoli, cabbage, or cauliflower which contracts club root fungus disease this year leave behind fungus to infect broccoli, califlower, or cabbage planted there next year. Tomato bacterial canker will persist in a viable state for three years, once it is introduced into the soil. Verticillium wilt fungus that infects a tomato crop one year will probably live in the soil for many years, and will infect subsequent crops of tomato, pepper, eggplant, and potato. There are vegetable varieties which can resist or tolerate infection by certain fungi and bacteria. Today, gardeners who know that their soil harbors Verticillium wilt, Fusarium wilt, and root knot nematodes can select tomato varieties that are resistant to all three diseases -- e.g., Carnival, Celebrity, and Santiago.

Tomatoes, okra, potatoes, and carrots are very susceptible to injury by the root knot nematode and favor buildup of this nematode in the soil. Sweet corn and other grasses suppress this nematode. Root knot nematodes do not usually infest onion, watermelon, or California # 5 blackeye peas.

Wireworms and white grubs thrive in grass turf, and a new garden plot will usually contain many active soil insects. Sweet corn, watermelons, and winter squash are better choices than the root or tuber crops for planting in newly tilled soil.

It is wise to plant a crop which favors

decomposition of organic matter after one which produces large

amounts of coarse organic material. Sweet corn produces

a coarse crop refuse that resists decomposition. The vine

crops: Pumpkin, winter squash, and watermelon and legumes such

as cowpeas accelerate the decay of crop refuse, and they grow

well following corn if triazine herbicides are not carried over

in the soil.

It is wise to precede shallow-rooted crops requiring close cultivation,

such as lettuce, beets, and other greens with clean-culture crops

such as tomatoes, peppers, summer squash, or melon, which extend

roots deeply into the soil and discourage weed growth by shading

the soil surface.

Some vegetables leave organic residues in

soil that are toxic (allelopathic) to certain crops which may

follow. Place crops in compatible sequence so that one which

produces a toxic effect will not precede one

that is susceptible to that toxin. Consider relationships

between sweet corn and some other vegetables. Decomposition

of sweet corn stubble liberates organic toxins which inhibit early

season root growth of lettuce, beets, and onions. Grain

corn and sweet corn are good alternate hosts for the fungus which

causes pink root disease of onions. Onions following corn

can have severe pink root disease even in soil where onions have

never been planted.

Certain vegetables feed heavily on available

nutrients, thereby creating a shortage for subsequent kinds

which are less efficient feeders. If celery is planted after

heavy feeders like tomatoes, close attention to soil testing and

fertilization is required to prevent nutrient deficiencies.

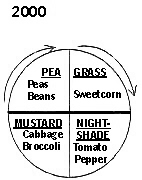

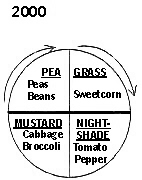

Expert vegetable growers and gardeners plan

rotations several years ahead. A rotation is easy to plan

and use. First, think of your garden in the circular shape

of a pie. Then draw a large circle on paper. Divide

the circle into 4 sections as you would cut a pie. The number

of sections you have will be equal to the number of vegetable

families that you intend to plant. A simple example would

be a garden with four vegetable families:

1) sweet corn (grass family), followed by 2) blackeye peas and

snap beans (pea family), followed by

3) cabbage, broccoli and radishes (mustard family), followed by

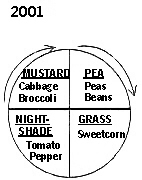

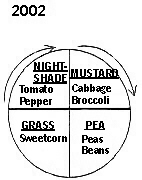

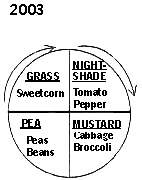

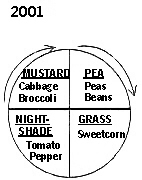

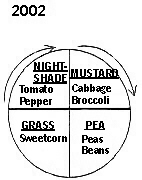

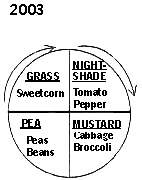

4) tomato, pepper and potato (nightshade family). To determine

what family will occupy the four plots next year simply rotate

the plan clockwise one section. Next year the blackeye peas

will be planted where the corn grew this year, and so on.

Other more complicated examples can be worked out using the same

procedure. Obviously, you may not want the same size plot

of every vegetable that you plant; but a well designed rotation

plan will help you avoid a helter skelter arrangement that would

cause trouble in the long run. (See illustration)

Succession cropping is planting two or more

different vegetables in sequence in the same garden space within

one growing season. The same reasoning and rules that were

used to explain rotation cropping apply

to successions as well. Succession cropping permits several

plantings of certain well liked vegetables without causing disease

buildup. For example, four or five separate crops of lettuce

or two to three separate plantings of beans or squash can be worked

into a garden inside a single season by an ambitious gardener

who plans ahead. One succession that has worked successfully

reads like this. In early spring, radishes, kohlrabi and

turnip greens (mustard family) are planted. Follow with

tomatoes and peppers (nightshade family), and finish out the season

with a seeding of beets, spinach and chard (goosefoot family).

Another planting plan could include lettuce in spring, squash

in early summer and broccoli in fall. Notice that in each

case the spring and fall crops are always frost tolerant, cool

season vegetables.

Intercropping involves the simultaneous

culture of two or more vegetables or a vegetable with a nonvegetable

plant in the same garden space within the same growing season.

Many combinations are possible. To keep a rotation sequence

in proper order, it is best to intercrop members of the same family

whenever possible. Radish can be sown between rows of transplanted

cabbage, broccoli and cauliflower.

The radishes will be harvested long before its slower maturing

companions take up the space. Bibb lettuce

or leaf lettuce can be planted between slower growing endive and

escarole. The lettuce will be harvested before the endive

needs the room.

The important thing to remember in intercropping

is to arrange spacing of different kinds of vegetables in a pattern

that will permit each to receive maximum light. When leaves

of one plant overlap those of another,

the ones which are shaded will grow less vigorously and be less

productive. For example, do not interplant marigolds in

your summer squash or tomatoes. Either the marigolds or

the squash will grow well, but not both. If you wish to

rid your plot of nematodes, plant it to sweet corn which nematodes

cannot use for food.

Always plant a winter cover crop of Elbon Rye where there is no

fall vegetable being grown to help control nematodes.

Expert vegetable growing is a complex discipline; but rotation, succession and intercropping plans that you make in advance of the season will pay off in your enjoyment of healthy vegetables.

|

|

|

|

|

Early Spring 2000 MUSTARD |

Tomato Pepper Eggplant |

Fall 2000 GOOSEFOOT |

|

Parsley Family Celery Celeriac Parsnip Carrot Parsley Fennel |

Mustard Family Broccoli Cauliflower Cabbage Mustard Greens Kale Kohlrabi Radish Turnip |

Gourd Family Cucumber (on trellis) Bush Buttercup Squash Bush Butternut Squash Bush Summer Squash |

The information given herein is for educational

purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names

is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended,

and no endorsement by the Cooperative Extension Service is implied.

Educational programs conducted by the Texas Agricultural Extension

Service serve people of all ages, regardless of socioeconomic

level, race, color, sex, religion, disability or national origin.

The Texas A&M University System, U.S. Department of Agriculture,

and the County Commissioners Courts Cooperating.